The Ghost Ship

Rupert Colley , published July 8, 2010. Link to Original

https://www.flickr.com/photos/historyinanhour/4775667526/in/photolist-8h1xzh-bh2Vfv-r21PLK-6g6YkY-s8hE3n-9NBCNP-9eg9RM-gUkrrW-dKN2Gw-gUkzJZ-2dv398-mhFonq-dNBxiN-dNBxdh-9Vytfh-8niNYV-apoLiZ-9ejeqf-b2qHg-dwfm7W-dR2Atb-qPbRWV-gf89Vv-7y5NfV-8xdjHk-arSZ2u-5QYHcN-gfbHUF-9Vytuf-gUkrzS-9VvCDn-dNvWM4-UnFvZy-9Vysjb-dNvWLX-ahcM5d-qcGNc-pmvGud-axFRBX-dgu1Ez-e9NHfC-gfb31U-c2hXTq-7Leeua-e9HeZX-jZTPk8-jZVpGT-qcGNb-rj8HwN-jZXVGs

Humanity is no stranger to the casualties of war. Stories of love and loss trickle through time and those who hold dear to them ensure the passionate wartime tales are told to generations. We are able to recount the horrific events our ancestors had witnessed or experienced. Hollywood as well, has become a platform for sharing warfare narratives, often times romanticizing the memoirs. But what happens to those whose stories are not shared? Do the lives lost ever inspire change? Does history lose a valuable lesson? Without genuine honesty in historical storytelling, humanity creates a catalyst of inevitability in repeating the same incidents over and over but, insisting on different repercussions. We need the past as much as we hope for a future. So, in an attempt to find a silver-lining in both, I’m pulling out a piece of forgotten history. A ship full of refugees, wounded Nazi soldiers and countless lost souls. It was called the Wilhelm Gustloff and this is its story.

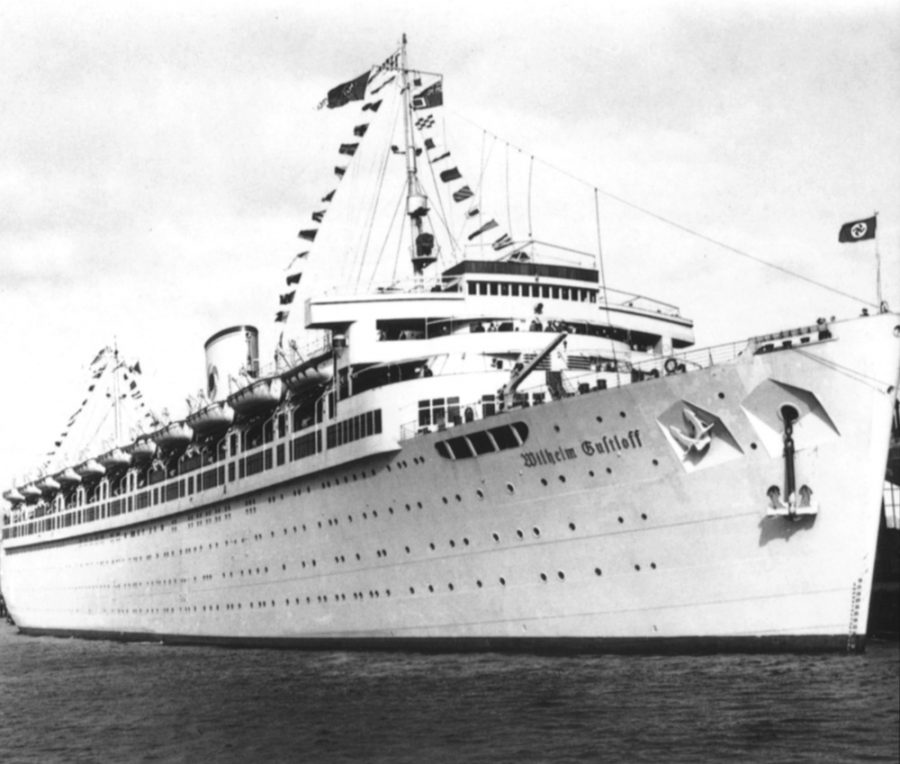

The Wilhelm Gustloff was constructed by Blohm & Voss shipyards in the year of 1936. She was originally to be named after Adolf Hitler but, instead was dedicated to Wilhelm Gustloff, a leader of the Nationalist Socialist Party’s Swiss Branch who was assassinated by a Jewish medical student in 1936. The Wilhelm Gustloff’s intended purpose was to be a cruise ship for the Third Reich. The five-deck ship was designed to hold about 1,463 passengers and made around 50 trips as a cruise line before being called to action after the breakout of the second world war. She began her military career as transportation for the Condor Legion after claiming victory in Spain. Beginning in September of 1939 she was converted into a hospital ship and was then altered to a barracks ship in November of 1940. Her role as an accommodation ship was over in roughly a year. The Wilhelm Gustloff sat in docks for four years until being called back into action as a refugee ship in the evacuation order of Operation Hannibal.

Operation Hannibal was the naval evacuation of German soldiers and citizens. However, Stalin’s troops were approaching from the east and for many the only way to asylum was crossing the Baltic Sea. Hannibal soon became the largest sea evacuation in modern history after Lithuanians, Lativaitvans, Estonians, ethnic Germans, and residents of East Prussia and Polish corridors joined in the movement to safety. An estimated two million people were successfully evacuated during the operation.

The official ship log stated 6,050 had boarded the Wilhelm Gustloff but, the list did not take into account the citizens who boarded without being recorded. After conducted research and numerous accounts from survivors, it’s been concluded the Wilhelm Gustloff was carrying approximately 10,573 passengers, over 8,000 of those being citizens. Compared to the ship’s capacity of 1,463, she was vastly overcrowded and due to the uncomfortableness, many did not wear their life jackets because of the body heat and humidity.

The Wilhelm Gustloff left the port Danzig at 12:30 pm on January 30, 1945, embarking on her journey to Kiel. She was accompanied by two torpedo boats and one other passenger ship but, due to mechanical problems, the passenger ship and one torpedo boat were unable to continue the trek.

The soviet submarine, S-13, commanded by Alexander Marinesko, slipped into the gulf of Danzig, after being informed of enemy activity on January 30, 1945. Marinesko quickly spotted the Wilhelm Gustloff’s lights and noted the military markings the vessel carried.

“And I was quite sure it was packed with men who had trampled on Mother Russia and were now fleeing for their lives. It had to be sunk, I decided, and the S-13 would do the job.” Marinesko stated.

Marinesko fired four torpedoes, each dedicated to different Russian propaganda. For Stalin was stuck in its launching chamber, the other three hit their target. The first, For The Motherland, struck the port side around 9:16 pm, causing a huge plume of water to shoot up in the air, killing the crew members resting in the lower area of the ship. The second torpedo, For The Soviet People, hit the swimming pool where 373 Woman’s Navel Auxiliary were resting . The torpedo blasted the tile of the mosaics, turning them into little pieces of shrapnel. The large glass ceiling above the pool as well, shattered, raining down on the girls as they slept. Of the 373 located at the pool, only two survived. The third, For Lengingrad, hit the engine room, taking out the power. The Wilhelm Gustloff was going down. Lights were out, titles were stripped. Humanity was at its rawest form, fighting for survival.

Those who managed to escape the trampling and were not already trapped in corridors of the ship, rushed to the top deck, trying to release the lifeboats. The twelve lifeboats were either frozen to their davits or ended up capsizing, plummeting the human cargo into the freezing waters of the Baltic Sea. The crew members, who knew how to operate the lifeboats, were already sealed off from the rest of ship, along with 1,000 other passengers, waiting for the drowning sensation the Baltic waters would greet them with.

The ship began to incline and many slipped into the sea from the ice covered decks. An SOS signal was made but, was only able to cover a range of 2,000 meters. Thankfully, the Lowe was able to pick up the distress call and furthered the message on, while quickly making her way to the sinking.

On the Wilhelm Gustloff people became more frantic and desperate by the second. Officers took their families into rooms, shooting all of them and then themselves instead of drowning in the the Baltic. Many had no choice but to jump.

The Baltic Sea was littered with bodies after the Wilhelm Gustloff fell to the depths of the icy waters. Children were drowned upside down due to the construction of the life vests. Those still grasping the tiniest bit of life reached for any piece of debris or a passing lifeboat, only to be batted away by paranoid survivors. In a span of 70 minutes, 9,343 people had died, making the Wilhelm Gustloff the largest Maritime disaster in history.

So why is this story only living in the past?

The Nazi regime did everything in their power to keep the whole incident quiet. Even though the majority of the losses were refugees (over 5,000 of the dead were children) they feared that any loss tied to their name could be detrimental to their already failing military campaign. The Russians as well, ignored the incident since Alexander Marinesko, was dishonorably discharged shortly after. Survivors were scarred from the horrific events they witnessed that night and it took time for many to find the right words and voice to tell the tale of a tragedy like no other.

The “Ghost Ship” as it has been coined, is still sitting at the bottom of the Baltic. Various diving expeditions have taken place since the sinking; the earliest, taken a few years after the incident, under Russian operations. In 1950, Russians cut into the Wilhelm Gustloff and did extensive searching, trying to loot anything they could, only to come up empty handed. Many believe they were searching for parts of the infamous Amber Room, said to have been smuggled onto the Wilhelm Gustloff. In the fall of 1988 German and Polish government declared the wreck site a war grave and memorial thus, ceasing further dives.

The 73rd anniversary of the sinking just passed. Survivors, relatives and historical enthusiasts look back at the calamity of the wreck and the impact it has had on, perhaps their own, as well as others’, lives. It is imperative stories like ones of the Wilhelm Gustloff are continued to be voiced by younger generations when the survivors can no longer speak. We may never be able to fully understand the hardships, but we have been gifted with the art of empathy. So listen, learn and teach. Each story weaves together to create our epic history.

Your donation will help support The Lambert Post, Lambert High Schools student-run newspaper! Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover website hosting costs.

Yasmeen Ketcherside • Feb 2, 2018 at 8:42 pm

Such a great piece Avery <3 Love your writing!

Sheila Franks • Feb 1, 2018 at 9:30 pm

Very well written and interesting. I wasn’t familiar with this story. Thanks for enlightening me. Keep writing.

Dad • Feb 1, 2018 at 7:36 pm

Great story Ave. Such a tragedy and an event which many have likely never heard of. Thanks for bringing it to life through you writing. Would make an epic movie.