Harm reduction: the answer to unhealthy drug use

Syringe Exchange Programs (SEPs) are just one way that communities can benefit in the name of harm reduction. Through these SEPs, individuals have a reduced chance of HIV contraction, areas have lower crime rates, and law enforcement has a lower chance of needle-stick injury by 66%.

Imagine your community being consumed by the harsh grasp of heroin. Just in your backyard, addiction has redefined lives and turned your local society into a cesspool for individuals to live off the pull of drugs. Teens are getting introduced to prescription painkillers and then getting lulled by drugs as fatal as heroin. This change in lifestyle was the reality for Georgia teen Taylor Smith. This popular high school cheerleader started her addiction by using prescription painkillers. It was the transition to the next level of opioids kike heroin that took her life on August 29th, 2013. At the age of only 20 years old, Taylor Smith had overdosed and had her future ripped away from her. Unfortunately, this tragic death is only one of many.

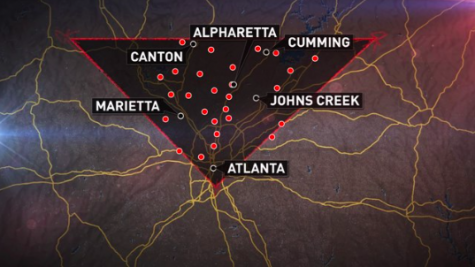

As a prime example of the expansive hold that opioids have on Georgians, a place deemed as ‘The Triangle’ instances the high rate of growth of heroin related deaths. The area stretches across the boundaries of Marietta, Johns Creek, and Sandy Springs. In 2016, an 11alive news team discovered a 4,000% increase in heroin related deaths broadening to Kennesaw, Acworth, Cumming, Cartersville, and Forsyth Counties. This fast growing rate of heroin-related deaths is represented in Atlanta’s northern wealthy suburbs.

When prescribed pain meds (e.g. Oxycodone or Percocet) for pain as a result of injury or surgery, people become hooked. But as the prescription disappears, the addiction does not. Forsyth County sheriff Duane Piper illustrates that “prescription drugs are tied with heroin” but “prescription drugs are more expensive and the supply of heroin from Mexico is cheaper”. Heroin has been acknowledged as the alternative to give people the same type of high while also feeding the addiction contracted from the prescribed pain medications. One threat of heroin lies within its lack of regulation and relatively easy access; without an identifiable potency, people face the threat of overdosing due to not knowing how much heroin is actually inside of the syringe.

This is where harm reduction comes into the solution: harm reducing treatment clinics give individuals threatened by addiction a chance to recover and redeem themselves. Georgia has 67 opioid treatment centers in which individuals from all over the southeast region (especially Tennessee, Alabama and North Carolina) are dispensed opioids such as methadone. I know what this sounds like: addicts having their addictions being fed legally. Treatment however involves allowing individuals to be tapered off the drug treatment while some patients have the option to stay on them for the rest of their lives. Jonathan Connell, head of the Opioid Treatment Providers of Georgia and three opioid treatment centers in southwest Georgia, advocates for the utility of combating opioid addiction with opioids as ‘people can depend on something, but not live an active addiction.”

Harm reduction can be seen as a practice that prevents the risks associated with illicit drug usage (e.g. ineffective drug policies, and addiction) without reducing the individual’s consumption.The practice is based on a range of core principles geared towards the utilization of no judgement, acceptance, dignity, and responsibility. The harm reduction philosophy realizes that change can be enforced and harm will be reduced through enacting healthy regulations, empowering drug users, and efficiently providing resources to communities. This progressive movement is also very unique compared to the current system that is now in place in the sense that, instead of objectifying people, this approach goes about to understand the realities of certain social injustices such as poverty, classism, racism, and sexism. This is very important considering that when change comes about nobody seeking aid will feel discriminated against.

This approach is exceptionally useful given that it makes drug users feel human again while also seeking to provide pragmatic solutions to potential drug-related risks (these risks include but are not limited to overdosing, contracting and spreading HIV/AIDS, automobile accidents, pharmacological-related health risks, withdrawal). In order for the desired result of reducing harm it is critical to educate communities and supply individuals with interventions. The harm reduction approach as a whole demands education; this strategy is one that can be utilized to provide individuals with accurate information on the consequences/risks associated with drug use while also providing behaviors that work to reduce the risk of potential drug use. The effectiveness of education however is limited without the implementation of interventions and counseling. Interventions prioritize the high-risk behaviors (injury, violence, and public disorder) associated with drug abuse typically through behavioural and cognitive therapy.

Education is a great preventative measure. Concerning those that are already using illicit drugs, harm reduction ensures that certain measures are put in place to minimize the risk that can come from further drug use. One of the major problems associated with drug use (usually associated with injection) is how it can increase the transmission and contraction of infectious diseases such as HIV. Through syringe exchange programs (SEPs), methadone treatments, voluntary HIV testing/counseling (HTCs), the reality of HIV and other infectious diseases progress to further threaten drug using communities.

SEPs and methadone in particular are rather significant to the approach considering their potential to help drug using communities and individuals. Methadone by is a harm reducing treatment option which has been shown to reduce overdose, risk of HIV, criminal acts and other high risk behaviors. Syringe exchange programs establish safe housing, employment opportunities, and sterile syringes. According to the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition (NCHRC), areas with SEPs are marked with a reduced needle-stick injury to law enforcement by 66% and a general decrease in crime rates. The effectiveness of SEP programs have also had a distinct international impact: Switzerland, the UK and Australia have showcased a reduced number of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs to practically zero. The potential that implementing both of these treatments bring to light is just another reason why harm reduction is so important to the future of threatened communities.

The idea of harm reduction has not been around forever. Originally conceived in 1980s Liverpool, England, a cauldron full of anger towards the “Establishment” translated into a thriving drug culture. The drug culture however was superseded by AIDS; the prevalence of AIDS and drug abuse proved to a catalyst for the harm reduction movement. Despite both of their presence, AIDS at the time was thought of as a greater threat to society than drug abuse. This contributed to the mode of thought that viewed drug abuse as something to not be prevented but accepted.

So Liverpool went through a massive drug reform: by implementing a free and limitless supply of clean needles, Liverpool transitioned from an area with only the minority injecting drugs such as heroin into the majority injecting. Peter McDermot, harm reduction activist, vouches for the importance behind harm reduction claiming the importance behind the “availability of legal supply of clean drugs and good supplies of sterile injecting equipment.” In other words, by implementing these programs across Liverpool, drug users limited their chance of receiving and spreading AIDS which halted the exasperation of the already out of control drug abuse problem.

I understand what this must sound like: the reforms in Liverpool were not working to reduce drug use but were rather working to encourage it. This thought process is most likely a result of the modern American justice system that primarily promulgates that the most efficient solution to drug usage and addiction is abstinence. But with the goals of harm reduction in mind, drug use and abuse is inevitable and should frankly be accepted.

Despite showing promise, not everyone perceives harm reduction as the most viable option when it comes to dealing with drug use; since the early seventies, abstinence has been the primary method preached and utilized by the federal government of the United States. Initially started by President Nixon, the war on drugs was a nation-wide declaration aimed at targeting and hindering drug use via expanding federal drug agencies such as the DEA. Unfortunately, this set the stage for the zero tolerance policies that were put in place in the eighties. With this battle against drugs at an all time high, the expansion of harm reduction faced a bleak reality.

What Nixon might not have been recognized back in the seventies was the potential for causing more harm than good. Logically speaking, the initial objective might have been thought to be reasonably obtainable, but thirty years later, the inefficient war on drugs has yet to have a distinguished victor. This is a result of the drug war policies that criminalize drugs while also criminalize minorities: the U.S. is less than 5% of the world’s population but is still 25% of it’s incarcerated population and nearly 80% of people in federal prison are black or latino.

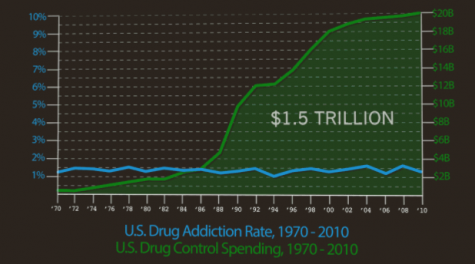

It is evident that the war on drugs has resulted in a racially disproportionate justice system, but the amount of money spent in relation to its intent is very concerning- especially in light of its results. According to data gathered by documentary film maker Matt Groff, a total of $800 billion has been spent since Nixon declared the war on drugs in 1971. With the rate of illicit drug addiction stable at 1.3%, a correlation between increased spending and the decrease in addiction should be expressed. Unfortunately, that is not the case.

The war on drugs has been teaching that the incarceration process possesses the ability to provide treatment within the criminal justice system. It has also shown an effective way to make profit: the incentive to prioritize cases that help police budgets results in law enforcement agendas focused on gaining assets as opposed to increasing public safety. This results in distorted law enforcement policies, unjust treatment of drug offenders, and the increased possibility of police corruption. This outdated way of thinking will only derail the United States on its path towards implementing a healthy and fair alternative to the war on drugs. Although this humanitarian movement is not embraced nation-wide, there are still many organizations that work to provide for communities and individuals struggling with illicit drug use.

So how do we make a difference? How does one go about to recover individuals that have been harmed by the war on drugs and even drugs themselves? The answer is simple: by creating and implementing harm reducing programs on a local level, communities that struggle with drug use and abuse can recover through safe, practical measures. Local organizations such as the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition (NCHRC) does just that.

The NCHRC is a organization that it’s committed to improving the community as a whole by advocating for a greater standard of health and marginalizing individuals. Under the harm reduction approach, people are supplied with educational services, risk reduction programs, diagnosis and treatment of substance abuse, and methods to combat the spread of diseases (HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and viral hepatitis).

Tessie Castillo, NCHRC’s advocacy and communications coordinator of six years, works to improve the health and wellness of individuals impacted by drug use. She vouches for harm reduction’s ability to “make a positive change” in people’s lives. “I have seen people who use drugs have hope for the first time that their lives can get better.”

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the various authors and contributors on this student-run news site do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of Lambert High School or Forsyth County Schools.

Your donation will help support The Lambert Post, Lambert High Schools student-run newspaper! Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover website hosting costs.