Here’s What Needs to Change In the War Against Drugs

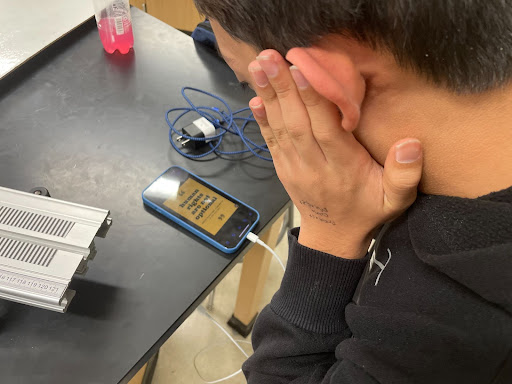

A Lambert student looking upon a poster for Amnesty International, concerned upon learning about the drug epidemic in the United States. Taken by Chitvan Singh on February 27, 2023.

As far as media coverage goes, the war on drugs is over. The policy initiative, a frontline issue just a couple of years ago, is now largely on the backburner following the pandemic. In the eyes of the public, the drug crisis, while still an important topic, is less known than global issues like the war in Ukraine and the national emergency in the economy.

Despite this extended hiatus of the war on drugs, drug abuse is still a major problem in the United States. And the worst part? Drugs seem to have won. The National Center for Health Statistics, a CDC agency, found that deaths resulting from drug overdoses increased significantly in the past decade, even through the pandemic.

On the other hand, anti-drug initiatives have been around for decades. In fact, they’ve started going into overdrive in the past two decades. The correlation between these two trends makes it obvious that our current drug initiative just isn’t working.

The term “war on drugs” has been around since the Nixon administration, and refers to the United States’ efforts toward drug prohibition and stopping the illicit drug trade. While there have been fairly successful attempts at stopping illegal drugs from entering the United States, it’s the first part of this plan that’s been fairly ineffective. Much like the prohibition of alcoholic beverages in the early 20th century, the prohibition of drugs in the United States hasn’t provided a long-term solution to combat their usage.

One focus of the prohibition policy for drugs is the punishment and, typically, the incarceration of drug users. However, a focus on incarceration doesn’t actually help victims of drug abuse. Sure, they’ll go to prison, but what then? Drug use is already rampant within prisons, and it’s likely that they’ll go back to drugs once they get out. Bureau of Justice statistics calculate that over two-thirds of those arrested for drug offenses are rearrested within 5 years. This means that incarceration is ineffective when it comes to solving the long-term drug problem.

So, if the punishment of drug users isn’t working, what needs to change? Even though it might seem counter-intuitive, what government agencies need to do is focus on rehabilitation for these victims, even if it means encouraging controlled drug use.

One important step towards this goal is repealing federal legislation that prioritizes the prosecution of drug crimes over rehabilitation for their victims. One such example of prosecution-centric legislation is Title 21 U.S. Code § 856, a federal law that makes it illegal to maintain premises that involve the use of illicit drugs. While this law does, in theory, assist in the prosecution of large-scale drug operations, it also limits what are known as supervised consumption sites.

Supervised consumption sites allow for controlled drug use in environments that contain trained healthcare professionals. Anyone who’s tried to quit an addiction will tell you that going “cold turkey” doesn’t really work. Supervised consumption sites motivate users to stop using drugs by helping them minimize their input in steps and learn how to quit, all while maintaining safeguards against overdose.

Unfortunately, this is just one example of how our drug policy limits rehabilitation. By adopting a zero tolerance policy for drug users, victims can’t actually quit. All they can do is face time.

Another issue originates from the nature in which the court system punishes drug offenders. Skilled as they may be, attorneys and judges are experts in the law, not in medicine. The criminal justice system often fails to understand drug offenders and what motivates them, from a psychological perspective, to continue usage. As such, a lot of drug cases are cut and dry. What this means is that rehabilitation isn’t even considered as a deposition.

Through the use of means such as plea bargains, drug offenders are given sentences that slightly differ from baseline incarceration charges. In order to achieve real change, it’s essential to pursue rehabilitation policies.

The clear solution is focusing on healthcare for drug victims instead of punishment. At Lambert, organizations such as Students Against Destructive Decisions and Amnesty International aim to spread awareness about actual solutions to the drug epidemic.

“The drug problem…needs to be resolved immediately in order to prevent further deaths,” Amnesty International officer Neharika Koppineedi said. “Rehabilitation is the favorable solution to help people.”

Organizations such as Amnesty club are pushing for jurisdictions to adopt decriminalization policies when it comes to drugs, allowing drug users to gradually quit through programs offered by actual medical professionals. The process of rehabilitation is a slow one. It won’t immediately solve the problem. But as the drug epidemic gets worse and the ineffectiveness of our current plan becomes clearer, a new solution is needed to truly fight this issue. It may seem like drugs won the drug war, but a change in strategy could help turn the tide.

Your donation will help support The Lambert Post, Lambert High Schools student-run newspaper! Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover website hosting costs.