“Student athlete,” a term coined in 1964 by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), was outlined not to encourage young athletes’ academic responsibilities but rather to define them as amateurs and, therefore, needless of fair compensation.

Collegiate athletes have increasingly criticized the label as exploitative, considering the contribution of student athletics to university recognition. While the NCAA passed the NIL policy in 2021, it only permits athletes to team with third-party brands and further deflects responsibility from the NCAA to pay its athletes directly.

This additionally puts less distinguished players with the same ‘student-athlete’ responsibilities as their standout counterparts at unfair grounds to compete for wages; it becomes a game of not what you do (practice and play) but how you do it (press interviews and social media).

Some argue that the NCAA’s provision of scholarships, particularly for Division I athletes, offsets their lack of conventional payment, but this does not speak for the 89% of varsity NCAA athletes that feel taken advantage of by the NCAA, according to a 2019 survey by College Pulse.

Just last year, a group of student-athletes filed a lawsuit against the NCAA and their respective colleges –Villanova, Duke and the University of Oregon– succeeding frustrations with the NCAA’s negligence to their independence while still refusing to label them as employees.

Though on the surface, the allegiance that ‘student comes before athlete’ interprets as agreeable, its preliminary meaning to take the spotlight off the “athlete” part as a means to withhold earnings has only grown difficult to defend. More and more athletes are openly opposed to NCAA policies, which they voice as robust expectations for both athletic and student performance while providing almost no assistance or reimbursement.

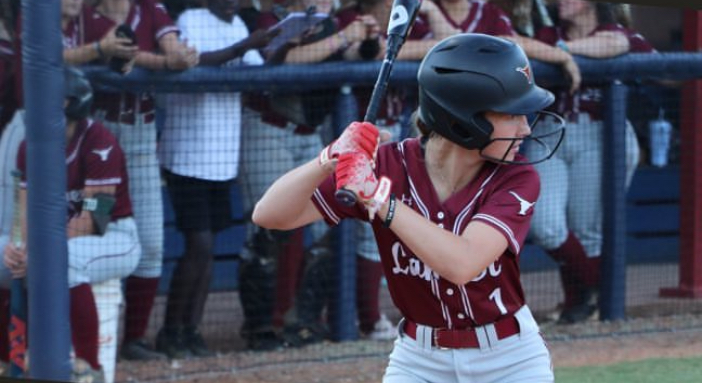

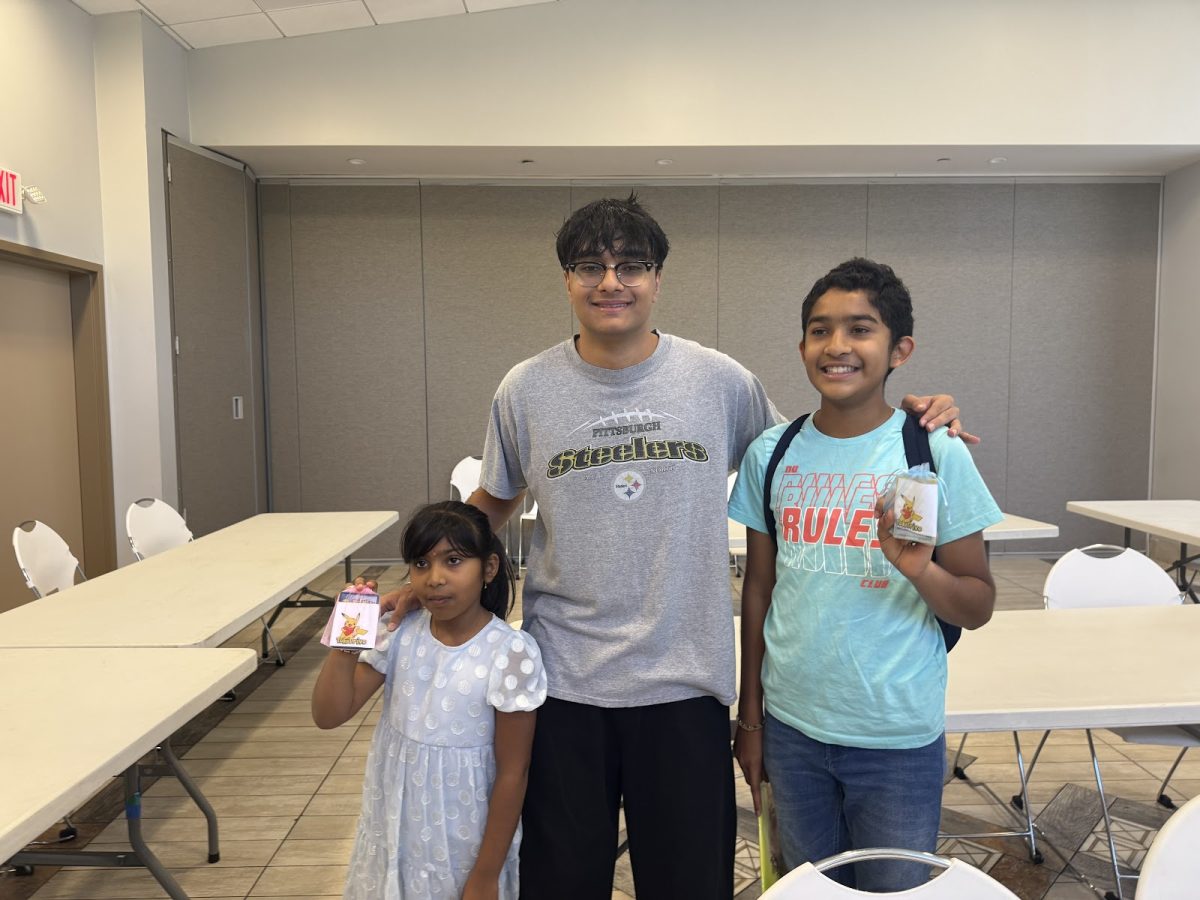

At Lambert, the quality athletic department can incidentally clash with student-athletes’ classroom performance. Three-sport athlete Bailee Jamison has occasionally struggled to manage the scholastic athlete framework.

“There have been some moments where I have been pressured [in]to being an athlete before being a student,” the junior revealed. “During my freshman year, I would miss study sessions that I needed to help me become a better student. I missed them because of various practices and the pressure to be the best that I could be.”

Jamison does not stand alone as roughly a third of student-athletes wrestle with balancing the two roles. It’s essential for schools to provide tangible resources for student-athlete progression, encompassing both titles- especially if we’re still lifting that phrase as credible.