The Racism Hidden Beneath Our Feet

In an effort to reveal the scars pervading Forsyth’s community, on January 24th in downtown Cumming the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) unveiled a memorial to a Black man that was lynched by a white mob in Forsyth County in 1912.

For a period of almost 75 years, Forsyth county was not only all white but also seen as dangerous for people of color due to the extreme racism. It was common knowledge amongst the Black community that living or even traveling in our county often resulted in lethal consequences. Many events in Forsyth County fueled the racist hatred of Black people. One event that left a lasting scar on the Forsyth community was the alleged rape and death of Mae Crow in 1912. This event caused a mass exodus of Black people from Forsyth and it began a century of white avoidance in the community. Many events in Forsyth County fueled the racist hatred of Black people. One event that left a lasting scar on the Forsyth community was the alleged rape and death of Mae Crow in 1912. This event caused a mass exodus of Black people from Forsyth and it began a century of white avoidance in the community.

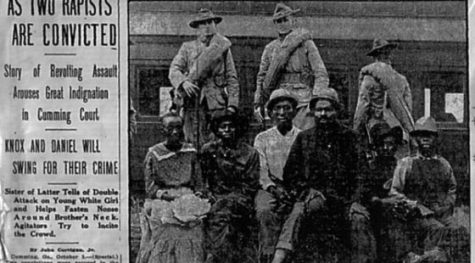

Mae was an 18-year-old white girl who lived in the old Forsyth. Allegedly she was hit on the head from behind, on what is now Browns Bridge road, and dragged into the woods where Ernest Knox, 16, is said to have raped her and then crushed her skull. She was found the next morning barely breathing and died soon afterward.

A pocket mirror supposedly belonging to Ernest Knox was found at the scene and he was then arrested and put into the Cumming jail; however, he was moved before a white mob was formed in an effort to prevent a lynching.

The next day Jane and Oscar Daniel, as well as Rob Edwards (all teenage friends of Knox) were taken to the Cumming jail on the suspicion of having information related to the crime. By the time they had arrived, a mob of more than 2,000 white people had already formed.

Later that day, the size of the mob had nearly doubled and proceeded to attack the jail. Some men gained entry and then shot Edwards dead in his cell. His body was removed from the cell by the men and then dragged through the street and mutilated to the point where it was nearly unrecognizable. His mutilated body was lynched on a telephone pole at the Cumming town square. The members of the mob were reprimanded by the sheriff but were never arrested or charged with murder.

After a short trial before an all-white jury, Knox and Oscar Daniel were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. The event was supposed to be private but the fence that was erected was burned down the night before, and it became a spectacle for nearly 8,000 onlookers.

In the months following these events, a group known as the “Night Riders” terrorized Black citizens and before long an estimated 98% of the Black population had left the county.

For nearly the next 70 years hardly any Black citizens remained in the county and it has been called one of the worst “racial cleansings” in American history. This period gave Forsyth the reputation of one of the most racist areas in the south.

After this long period of silence in a whitewashed county, racial tensions suddenly burst through the roof yet again in 1987. This occurred after a small march through Cumming led by Hosea Williams on the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday. The gathering met resistance in the form of bottle and rock-throwing counter-protesters.

The incident with the small procession of marchers alongside Williams received attention from across the nation, and the following weekend a group of nearly 25,000 demonstrators descended upon cumming. The congregation of people swarming towards the county completely shut down the highway from Forsyth to Atlanta. The gathering was so large that troops from the national guard were present in case of the event of violence. Violence would have been very likely without the protection that the state and national guard provided considering there were nearly 1,000 counter protesters.

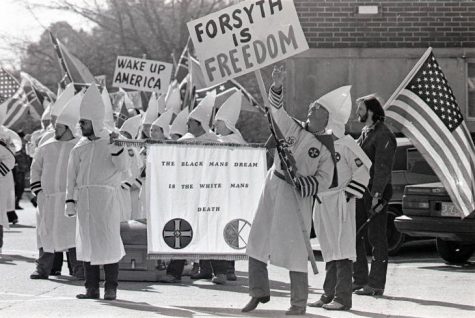

This was the beginning of a slow end to the complete racism that persisted in our county’s roots; however, there was still clear opposition for a long time. For example, in 1988 there was a public rally of the KKK in downtown Cumming supporting segregation and racism while singing “Dixie” by Daniel Decatur Emmett. A confederate song used by racists during the civil rights movement due to its offensive stereotypes towards African Americans.

Events like this can be seen constantly in our county’s history, and while the county has progressively gotten more diverse than ever, it has taken time. Back in 2010 The county’s diversity, while more diverse than 99.9% white with a small handful of Black citizens as it was in the 1970’s, was still vastly white with around 85.43% of people being white and only about 2.57% Black. While still unbalanced the racial dispersion of our county continues to slowly neutralize.

Thanks to the efforts of the EJI, memorials like the one in cumming have been placed all over the country to help our country truly end the racism that persists in its roots. Now, more than a century after Mae Crow’s untimely death, the scars on our community have finally started to heal, letting us extinguish our racist roots and move into a future for everyone.

Your donation will help support The Lambert Post, Lambert High Schools student-run newspaper! Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover website hosting costs.

K Bryant • Mar 4, 2021 at 3:12 pm

Thank you, Colby, for an excellent article!