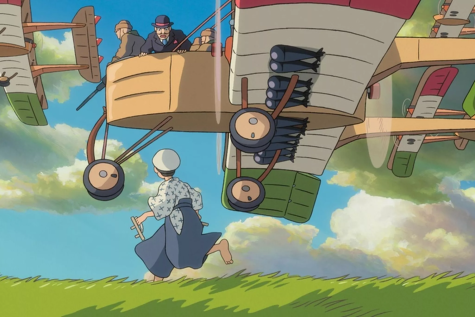

‘The Wind Rises’ Movie Review: Make Love, Not War

I recently decided to watch some Studio Ghibli films, those of which are generally reputed for their charming stories and gorgeous 2D animation. I had always known of these movies, regularly seeing references to My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and Ponyo. These films have a beautiful yet straightforward Japanese animation style, alongside some unrealistic character designs, so I always thought all Ghibli films were just kids’ movies. When I watched Hayao Miyazaki’s 2013 masterpiece, The Wind Rises, I quickly realized this was an extremely incorrect generalization. As ironic as it is, this movie blew me away.

If you haven’t watched The Wind Rises, I highly recommend it before reading this review.

Major spoilers below!

The Wind Rises is a fictionalized biographical film of Jiro Horikoshi, a Japanese aeronautical engineer during the WWII era. While a few of Jiro Horikoshi’s real-life aspects are kept accurate, the majority of story elements are changed to better suit the movie. Regardless, the film’s basic premise follows the same events that occurred in Horikoshi’s life, which mainly revolve around his dedication to his work as a top engineer for the Mitsubishi A5M in WWII Japan. The movie additionally has a heavy focus on Jiro’s love life, as well as themes regarding the distribution of time between work and love altogether.

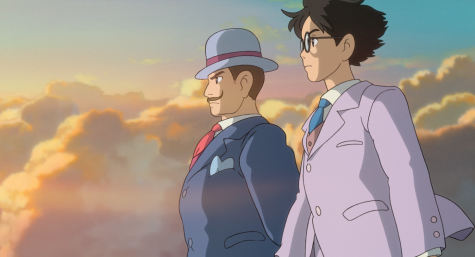

The beginning of the film introduces us to Jiro’s fascination with planes, and his obsession with the famous Italian engineer Giovani Battista Caproni, who wanted to create airplanes for the joy of flight, not for war. Caproni repeatedly manifests in Jiro’s dreams at critical points throughout the movie, and it’s his appearance that solidifies Jiro’s intentions in life. Due to his nearsightedness, Jiro is incapable of piloting the planes himself. Still, Caproni assures him within a dream that even a masterful engineer such as himself has never flown a plane. Jiro becomes an extremely prominent figure in the Japanese engineering community, and as the film progresses, the implications of his work become more meaningful. It’s Jiro’s dedication to this dream that drives him to his status throughout the movie.

There are a handful of supporting characters in the film that all tie into Jiro’s life in one way or another. A majority of the side characters are Jiro’s coworkers and bosses from Mitsubishi and engineering school, but Jiro’s own family and his love interest are also present. While some may have viewed the developing side characters as a distraction from Jiro, I greatly appreciated how beautiful and complex everyone’s story was.

Kiro Honjo is portrayed as one of Jiro’s best friends, who is obsessed with the development of Japan during the war years. He continually sees the country as backward and poor due to shoddy reconstruction, failed flight tests, and the cheap wooden/papercraft engineering that the team is forced to utilize. Honjo travels alongside Jiro to Germany to modify a full metal plane with bombs, only to be continuously denied access into the plane’s interior. “Frustration” sums up Honjo’s initial character, and Jiro’s almost oblivious reactions add a bit of humor to the film. Honjo’s nature directly contrasts that of Jiro, yet their duality forms such a perfect friendship.

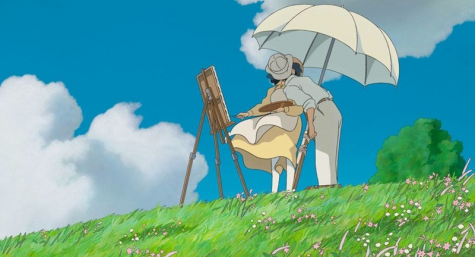

Naoko Satomi is another major character in the film, as she ends up being Jiro’s wife. Initially meeting Jiro on a train during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Naoko is forever indebted to him for saving the life of her maid. The two eventually meet again at a Summer Resort as Jiro rests from a failed flight test for the Imperial Navy. This encounter marks the schism in which Jiro realizes that his dream is not everything. He falls in love with Naoko, and this drastically changes him, even though his devotion to the Japanese flight program is quintessential towards winning the war. As Jiro labors, far from Naoko, she suffers a lung hemorrhage, and ultimately can’t bear being away from him. As her health deteriorates, Jiro devotes more and more time away from his work. I generally don’t enjoy the cliche of a working lover spending more time with a dying partner, but it’s the crucial implications of Jiro being away from designing planes that makes this theme so powerful. Jiro’s intense passion for the creation of flying machines isn’t enough to overcome his love for Naoko, and it’s the sheer amount of time that the movie spends developing that passion that makes his love for her so much more meaningful.

Jiro’s construction of the Mitsubishi A5M fighter is what he’s known best for, but all Jiro ultimately wanted was to create a beautiful aircraft. Every setback, every inconvenience, and failed test only furthers his passion, and with his desire to stay with Naoko, Jiro becomes a character with a goal one can sympathize with. With a strong gust of wind, It is presumed Naoko is dead during the final test flight for the A5M, leaving Jiro in a trance while everyone else celebrates wildly. The film ends just as history did, with Japan losing the war, despite Jiro’s success. Caproni manifests in Jiro’s dreams once again, overlooking the carnage of war. As Jiro describes his regret for creating something that was ultimately used for slaughter, Caproni consoles him with the fact that he fulfilled his dream of creating the perfect plane. Naoko manifests as well, exhorting her husband to live his life to the fullest.

I have nothing but praise for the character development in the movie. The film takes place over a multitude of years, and even though Jiro is an extraordinarily focused and simple-minded character, he still manages to be dynamic. I marveled at his character development, wherein his coworkers ridiculed one scene for actually wanting to get married. “So he’s actually human?” It’s one of the few scenes where Jiro gets angry (or portrays emotion at all), yet it doesn’t feel out of place. Honjo also develops throughout the movie, initially questioning how much Jiro stares into space and focuses on “Mackerel Bones,” to ultimately admiring and respecting his talents. Having reliable and meaningful character development in a mere two hours or so is generally a challenge for most movies, but this is a rare exception.

I also admire the historical setting of the whole movie. A Japanese perspective during WWII is incredibly exciting, as the country is frequently regarded as being “10-20 years behind” based merely on the aircraft industry. The war also characterizes Jiro indirectly, while still managing not to be the predominant focus. Jiro’s aversion to violence is not frequently addressed, yet rather implied. Historical events are also subtly placed throughout the film, not as a distraction, but more as immersion. It makes sense that Jiro idolizes Caproni specifically, as the foreign aircraft magazines Jiro read as a child were imported from Italy. On his visit to Germany with Honjo, Jiro witnesses blatant Anti Semitism on a midnight stroll. Yet the movie never dwells on these allusions of war, and I frankly don’t think it needs to: there is no need to display Jiro’s hatred of evil continually, and it’s this entire background of war that feels so relevant, yet isn’t at all. I seldom expect a war movie to be about anything shy of dehumanization, politics, and trauma. However, this movie pulled it off perfectly.

Overall, The Wind Rises is a tragic yet beautiful tale of a man’s dream and the turbulent winds that set it into motion. Studio Ghibli truly poured their heart and soul into this film, and it shows. While I do think the resolution is quite sad, I wouldn’t have wanted it to end any other way. The Wind Rises was Hayao Miyazaki’s last film before he retired in September of 2013, but he announced in 2017 that he would be directing ‘How Do You Live?’ expected to be released in 2020 or 2021. If Miyazaki directed this masterpiece, I will be sure to check out his future work.

Side note: Frozen got an Oscar, but this didn’t. Thanks for nothing.

Your donation will help support The Lambert Post, Lambert High Schools student-run newspaper! Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover website hosting costs.